The Hidden Costs That Engineers Ignore

“It’ll only take me a few hours to implement the feature,” we sometimes say. But after finishing, we find that every few weeks, we’re either fixing a bug with the feature, explaining it to another engineer, or helping answer a question from customer support about how it works. The total investment of time to maintain the feature far exceeds the initial few hours of development.

One of the hardest lessons to internalize in software engineering is the hidden costs of additional complexity. Sometimes, complexity is just inherent in the problem space. Matching passengers and drivers while adjusting prices to balance supply and demand is a complex and hard problem. So is routing questions and answers to the people most likely to answer and read them while scaling a community and maintaining quality. Or developing a rich document editor that works well across all devices and supports real-time collaboration. That’s the inherent complexity that we need to tame for the products to succeed.

But other times, the complexity that we wrestle with is complexity that we introduced ourselves. We wrote code in a new programming language that few people knew and now we have to maintain it. Or we added additional infrastructure because we wanted to try the new, hot technology stack that we read about on Hacker News, but it fails in ways that we didn’t initially expect. Or we introduced a feature that few people use but that consumes a disproportionate amount of our time through fixes and bug reports.

Additional complexity imposes many hidden costs. The decisions we make when building software don’t just determine our current development speed. They also have repercussions on how much time and effort we spend maintaining it going forward.

The Hidden Costs of Complexity

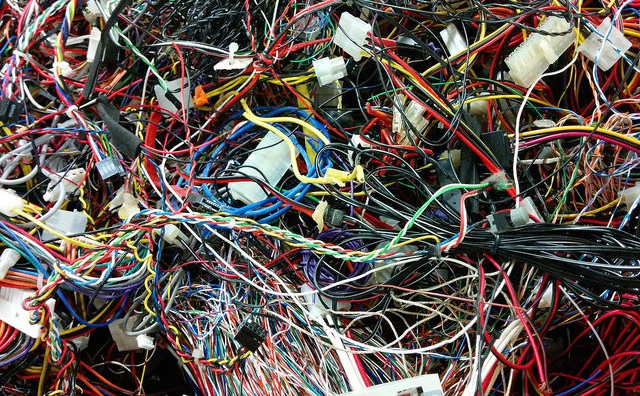

Too much complexity increases cognitive overhead and introduces additional friction to getting things done. It seeps through a team in a number of different ways — most directly through code, system, and product complexity but indirectly through organizational complexity. Let’s look at the hidden costs of these different types of complexity one by one.

Code Complexity

Code complexity doesn’t just grow as a linear function of the number of lines of code — it grows combinatorially. In a complicated codebase, each line of code may interact with and affect many other lines of code. It’s difficult for us to wrap our minds around combinatorial growth, which is why we tend to significantly underestimate the time it takes to complete large software projects. That’s a major reason why rewrite projects sometimes slip their schedules by wide margins.

When code is too complex, it becomes harder to ramp up, harder to reason about it, and harder to fix bugs. It’s difficult to untangle the dependencies and data flows to track down the source of errors. Engineers may actively avoid the most complex parts of the codebase, opting to work around it even if it’s the most logical place to make a certain change. Or they may avoid working in those areas all together, even if the work can be high-impact.

System Complexity

Engineers like tinkering with new toys, whether it’s because they’re curious or because they think that a new technology might provide a silver bullet for solving one of their pressing problems. When Pinterest was initially scaling their site back in 2011 to handle rapid growth, they used 6 different storage technologies (MySQL, Cassandra, Membase, Memcache, Redis, MongoDB) across a backend team of only 3 engineers. 1 Each new technology they experimented with promised on paper to address some limitation of their existing system. But instead, they found that each new solution just failed in its own special way and took more time and effort to manage and maintain. Eventually, the team learned that it would be simpler to scale by adding more machines rather than more technologies, so they eliminated systems like Cassandra and MongoDB and strengthened the remaining components of their architecture.

Fragmenting infrastructure into too many systems brings many hidden costs. Attention gets splintered across the multiple systems. It becomes harder to pool together resources to build reusable libraries for each system, harder to ramp up new people for pager duty, and harder to understand the particular failure modes and performance characteristics of each system. The abstractions for each system end up being weaker because there isn’t as much time invested in each one. When tools and abstractions are too complex or there are too many of them, they become difficult for the team to understand and discover.

Product Complexity

Product complexity can result from an ill-defined vision or an untempered ambition leading to a lack of product focus. This desire to be great at many things instead of just one core area sometimes manifests itself in an inability to concisely explain the purpose of a product to new users. Product complexity leads to more code and system complexity — teams add more code and more infrastructure to support new features. When a product has a wide surface area, adding a new feature or modifying an existing one requires expending a large amount of effort to understand and accommodate the olds ones.

An overly complex product means that there are more code branches, more issues to think through, more bug reports that the team needs to address. Engineers and data scientists need to analyze more variables and do more one-off reports, rather than focusing on understanding core user behavior. Engineers need to invest more time to ramp up on the feature space and be productive. Everyone ends up context switching between more projects. And the time spent maintaining all these features is time not spent re-investing in the code, repaying technical debt, or strengthening abstractions.

Organizational Complexity

Code, system, and product complexity in turn breed organizational complexity. Teams need to hire more people to tackle and maintain everything that’s been built. Larger teams mean more communication overhead, more coordination, and lower overall efficiency. The hiring process itself, with all the interviews and debriefing, can consume large portions of the team’s time. And, of course, all the new hires have to be trained and onboarded.

The alternative to hiring more people is splitting the engineering organization into smaller teams — perhaps even creating one-person teams — to cover the large code, system, and product surface area. This reduces the communication overhead, but one-person teams have their own costs. It’s easier to encounter roadblocks that completely stall the sole person on a project, and because there are fewer people to share those troughs with, the experiences can be more detrimental to morale. There are fewer opportunities to work with other people, which can hurt workplace happiness and employee retention. Unless everyone is conscious and proactive about asking for feedback, individuals might receive less feedback about their work because there are fewer people who share the same project context. The reduced feedback can lead to lower quality code or inadvertent complexity being introduced into the codebase or infrastructure.

How to Fight Complexity

Tony Hoare suggested in his 1980 Turing Award lecture, “There are two ways of constructing a software design: One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies and the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies.” Having discussed how the non-obvious deficiencies due to complexity can hurt us, how do we go about defending ourselves against these costs?

Here are some strategies you can use:

Optimize for simplicity. Resist the urge to add more complexity. Reason through the maintenance costs. Ask yourself whether the complexity introduced by tackling the last 20% of the problem is worth it, or whether the 80% solution suffices.

Define a mission statement for your team or product to align focus. In Team Geek, Brian W. Fitzpatrick and Ben Collins-Sussman explained how they had mentored the Google Web Toolkit (GWT) team and encouraged them to write down a mission statement. The ensuing debate over the content and style of the mission statement revealed that the lead engineers didn’t actually agree on the product direction! They were forced to confront and reconcile their differences and ultimately came up with, “GWT’s mission is to radically improve the web experience for users by enabling developers to use existing Java tools to build no-compromise AJAX for any modern browser.” How much fragmentation of efforts would have followed if they hadn’t hammered out the differences sooner?

Compose large systems from simpler building blocks. Google is an example of an organization that focuses on building strong, core abstractions that then become widely adopted for a wide variety of applications. They have basic building blocks like Protocol Buffers, the Google File System, and Stubby servers for remote procedure calls. On top of those building blocks, they’ve built other abstractions like MapReduce and BigTable. And on top of those, thousands of applications including large-scale web indexing, Google Analytics site-tracking, Google News clustering, Google Earth data processing, Google Zeitgeist data analysis, and many more are then built. 2 3

- Clearly define interfaces between modules and services. Decoupling modules and services reduces the combinatorial complexity that can otherwise grow out of a pile of code. At Amazon, Jeff Bezos decreed in 2002 that the company would move toward a service-oriented architecture and that all teams would communicate with each other only through service-level interfaces. 4 While the transformation came with its own set of huge development costs, it enforced separation of code and logic behind services and facilitated the creation of its now highly successful Amazon Web Services.

Periodically pay off technical debt. We’re always building software under incomplete information. As a codebase grows organically in response to changing conditions, entropy also increases. The increased complexity becomes a tax on future development. Budgeting time in development schedules can help reduce that cost. Many engineers and teams budget that time between projects, but holding one-off events can also help. At Quora, I once organized a Code Purge Day where engineers focused on deleting unused code in the codebase. We tracked the progress of code purging on a leaderboard, which made it much more fun than deleting code on your own.

Use data to prune unused features. At Yammer, when engineers or product managers found that enhancing a feature or preserving it in a code refactor would take a non-trivial amount of effort, they would look at usage data to see if the feature was actually used. If not, they’d decide with the team whether they ought to just cut the feature to reduce overall work. 5 This strategy reduces product debt in a similar way to how simplifying code reduces technical debt.

- Group ongoing projects around themes. This enables teammates to share the same context as each other, which makes it easier to engage in design discussions, review code, or build reusable libraries. All of these activities help provide checks and balances that individual engineers may other introduce.

When we build software for a school course, we get an oversimplified view of the world — the costs of maintaining any complexity disappear at the end of a class. But in our careers, poor software decisions can impose a tax for years to come.

Don’t complicate things.

Todd Hoff, “Scaling Pinterest - From 0 To 10s Of Billions Of Page Views A Month In Two Years”, High Availability. ↩

Jeffrey Dean and Sanjay Ghemawat, “MapReduce: Simplified Data Processing on Large Clusters” ↩

Fay Chang et al, “Bigtable: A Distributed Storage System for Structured Data” ↩

Steve Yegge, “Google Platforms Rant” ↩

Kris Gale, “The One Cost Engineers and Product Managers Don’t Consider”, First Round Review. ↩

“A comprehensive tour of our industry's collective wisdom written with clarity.”

— Jack Heart, Engineering Manager at Asana

“Edmond managed to distill his decade of engineering experience into crystal-clear best practices.”

— Daniel Peng, Senior Staff Engineer at Google

“A comprehensive tour of our industry's collective wisdom written with clarity.”

— Jack Heart, Engineering Manager at Asana

“Edmond managed to distill his decade of engineering experience into crystal-clear best practices.”

— Daniel Peng, Senior Staff Engineer at Google

Leave a Comment